Here are brief notes from the weekly practice discussions and other thoughts. Feel free to post comments by clicking the date.

- 5/10/2025

Congratulations Sharon/Sujata and Gina/Sakula!! On receiving Theravada Buddhist precepts as a Dhammacari (ordained lay Buddhist teacher) from Bhante Piyananda at Dharma Vijaya Temple in Los Angeles on Vesak/May 10th.

It’s a recognition of your accomplishment on following Buddha’s path, a commitment to being a good person for yourself and others, and accepting a role where you can lead as a Buddhist teacher.

Both have been excellent meditators and listened to me teach for the past 7 years. Now they have valuable insight and loving hearts to share. Proud and happy for you!

Eric/Bodhi

- 1/25/24

Meditation is not escape from what we don’t want to face.

Meditation is not indulgence into ecstasy.

Meditation practice is learning to restore our contentment faster.

The main way to do that is to recover/discover our sense of self.

You are more than you think you are and it’s wonderful. - 12/18/23

I reviewed WAKEFUL pages 26-51 where the practical aspects of meditation are described. The pages after that are focused more on the challenges of meditation once you start practicing. WAKEFUL was Sensei’s expression of traditional Buddhism. Over the years he started focusing more on being than on meditating, saying “be happy and strong” instead of “just meditate”. Still I think we struggle and get in a rut as we learn to be happy and strong, and confrontation as you do in meditation helps us come to our senses with a more accurate self-perspective.

- 12/11/23

WAKEFUL (pp 1-25): We had an excellent discussion on many ideas and ways of expressing them here. One thought I had about the middle path between the two ways forward that Sensei talked about in this section and the extremes Buddha experienced as a sheltered prince and later as a wilderness ascetic. Should we seek comfort or should we seek to overcome pain? The answer is: that’s irrelevant, we should seek to know ourself. This is much like ‘before enlightenment chop wood carry water, after enlightenment chop wood carry water.’ Daily life continues before and after we know what and who we are and we stop being attached to what we are not. We are so much more than we think. We’ve often settled on being the cheap dragon; of being a comfort-seeking being. There is more to you than that. Dogen Zenji says: “Please, honored followers of Zen. Long accustomed to groping for the elephant, do not be suspicious of the true dragon.”

- 12/4/23

The Buddhist “version” of Santa Claus is the Chinese Buddhist monk, Pu Tai (=Hotei in Japanese), which you see as the common big-bellied Buddha statues. The Happy China-man has a story in 101 Zen Sayings (Zen Flesh Zen Bones). The significance of Jhana (=Zen in Japanese)? stop and pay attention. The realization of Jhana? just continue on. They say before enlightenment chop wood carry water, after enlightenment chop wood carry water. Meaning what you do doesn’t change, it’s how you experience it: without attachment. We’re going to do a book club type study, initially with WAKEFUL starting next week.

- 11/27/23

Joseph Campbell (1904-1987) wrote a pivotal book called The Hero with a Thousand Faces where he pointed out commonalities between various religious stories. The idea taken from that of the Hero’s Journey seems to fit many “coming of age”- type fictional stories like the Ramayana, Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, various superhero stories, etc. It doesn’t fit others such as tragedies and comedies like Hamlet and Oedipus. Also, I’m not sure it fits Gilgamesh or Beowolf either, though they are ancient heroic epics. The Hero’s Journey, however is clearly an archetypal story and part of our human collective as Jung described, and is a useful story-structure to consider for our own life-story. We might even look at our relationship with meditation in this way. How did you first encounter the idea of meditation? What made you decide it was something you needed to do? As you learned to meditate when did you stop searching here and there and realize you just needed to practice? What was your impossible challenge that you overcame? how was your first experience of jhana? then after that how did you see yourself as a different person? Did you share your new experience with those who were with you when you started the journey? Personally I’ve gone through the full circle with Chapel as my starting/ending point. Maybe I’ll write my own little epic someday. Think about writing yours, even just for yourself.

- 11/20/23

A basic message of Buddhism is that our attachments create our suffering so we should meditate. But why? It’s because meditation is training to develop our relationship with our own wants and don’t wants. That is, how do we act, feel, think about the things we want to have or want to avoid in our life? It could be that we feel greedy, needy, unworthy, pessimistic, entitled, or any other form of not so healthy relationship. So what is a mature relationship then? Well, we’re happy when we encounter good things and unhappy when we encounter bad things; that’s simple enough; mature and healthy you might say. But when we are seeking, exerting our effort, and working for our goals that we have some expectations positive or negative based on various things. Here it makes sense that patience/persistence (khanti) is a good thing. Generally speaking, we can be happy in our goal-oriented efforts and at the same time not insist on getting a result. In a sense it’s like being respectful of the Universe to respond as it will to our efforts, and recognizing that we are not in absolute control. Should we create the life we want or discover the life we should have? Neither. Forcing life to meet your expectations is bound to fail, and allowing life to pass you by is also bound to fail. The answer is that the question is incorrect. Instead of asking ,”should you create or discover your life?”, how about, “what attitude shall I have as I strive for what I want?”. There are a lot of ways to think about your relationship with what you want to have or avoid. Generally a conscious pause can help you see how you are holding your mind. Meditation is just such a pause.

- 11/13/23

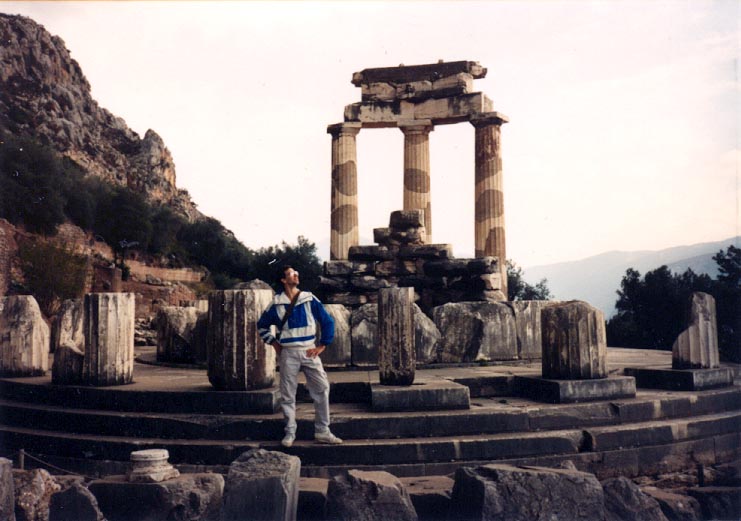

I learned an Ancient Greek phrase today watching a history documentary: “Kalos/Kales Kai Agathos” = he/she is beautiful/noble/handsome and good/virtuous/dutiful/brave of character. How do we be that? What about “Find Your Bliss”? This common phrase started with Joseph Campbell (famed for the idea of Mythical Archetypes) and is nicely explained in this Psychology Today link: “Sometimes people equate bliss with being in a state of euphoria, but in reality, being blissful is the state you’re in when you’re doing whatever instills a profound sense of joy within you” It was initially referring to finding your life or career path. So I might replace “bliss” with purpose or better yet contentment: find your contentment. Commonly we work to attain circumstances that match our vision and if we succeed for a time, then we feel content for that time. But don’t we try to do this in meditation, despite circumstances? So I’d also replace “find” with “create” because it’s not a passive or lucky thing at all. Circumstances require some luck, but in the long run “create your contentment” is how we can grow to be a content person regardless of circumstances. How? by holding your mind steady. That’s fundamental to the process. It could be while jogging, watching the sunset, meditating, etc. The other things we do in meditation that are helpful are: refrain from effort, pay attention to now, wake up, relax and let go, etc. As we practice and develop a greater capacity to be a content person, we become more aligned with our personal purpose and values, and that brings out the best in us. We become kalos/kales kai agathos: beautiful and virtuous.

at Delphi, 1990

- 11/6/23

After this weekend’s retreat I’m thinking about 3 things that meditation typically does for you. 1) After an exciting or upsetting day, meditation settles us down. In my experience, that can take anywhere from a few minutes to several hours of zazen, depending on your day and how your life is going. Years ago the first hour of my two-hour practice was always a settling time, but I’ve gotten better at it and now typically I’m settled even before I ring the bell. 2) The next thing meditation does for you after you are settled down, is re-center your perspective. I find this happens after a day or two on a meditation retreat. It takes time to fully disengage our mind from all the efforts we are juggling – both consciously and subconsciously. But when we do, things stop getting blown out of proportion. 3) Then what do we get out of a longer meditation retreat? I’ve found that most people hit a point of difficulty after about 2 days (maybe 1 to 3 days) where continuing is very difficult. This is confrontation as Sensei often said. This is when specific personal issues and crises arise. Our mind is working perfectly by bringing the most urgent things to our attention. And when we give it a couple days focus and spaciousness on a meditation retreat, we might suddenly start crying and not understand why until later.

Of course we might be living daily with this confrontation already. These are our personal koans, like a conflict of values; which way do we go? what can we say? How can we help our suffering loved one? what “should” I do? Facing it in our mind is a requirement for getting through it; of being resolved in how to proceed; of ending our internal struggle. Maybe there actually is no solution as we’ve framed the problem. In some cases we can’t help our loved one, but we can be present with them so they are not alone. When we realize this is the truth for those cases, then we feel confident, clear and strong with how we move forward.

- 10/23/23

The Catholic Cathedrals in Italy were beautiful, and learning details of those stories showed me that GRACE is maintaining your self/values despite suffering. It’s like the word METTLE, meaning “the ability to meet a challenge or persevere under demanding circumstances; determination or resolve.” It’s human to lose ourself in reaction, and the growth out of that is our path forward. The Buddhist 5 hindrances is a convenient list of common reactions; in my words: indulgence, anger, depression, anxiety, confusion. Personally, I typically react with anxiety because of the personality that formed from my own upbringing, genetics and past lives (i.e. nature vs. nurture) to various degrees. But I do fall into the others, and in the past month have felt some frustration (a shade of anger) a few times. Noticing myself when that happens is a kind of “observation-meditation” (often labeled vipassana), and is basically just being mindful/present (sati). One universal observation is that we tend to lose ourselves more often when we have less extra space or energy before we reach our limit, for example when we are sick, in pain, exhausted, sleepy, or generally when we are suffering. Those are the demanding circumstances that test our mettle, and that’s when we can put extra effort into being present and perhaps reach a state of grace. When we meditate we similarly face a demanding circumstance, and it can be the exact same thing like an injury that captures our attention. But beneath those layers there’s a fundamental conflict we must face and resolve: how content are you willing to be right now? Ultimately we can go beyond grace into glory, but we have to be wiling to give up our self and trust in Nature/God/the whole.

- 10/2/23

The Bhagavad Gita is a short story expressing Hindu philosophy and one of the ancient foundational texts of the religion. It expresses the Samkhya philosophy upon which Patanjali’s yoga is based, that the fundamental essence of things is a mixture of three characteristics: Sattva (air, reflection), Rajas (fire, activity), and Tamas (earth, inertia). You might recognize this as the basis of an Ayurveda diet (see Deepak Chopra). So you can consider yourself to be more often Rajasic, or Tamasic, or Sattvic – busy and can’t stand still, lazy and hard to get going, or accommodating and uncertain. And as you sit to meditate you may find the same typical difficulty faces you accordingly. So let me talk about how a rajasic person might overcome the obstacle in order to meditate. In that case, consider, what would you rather be doing this evening rather than sitting and waiting to go to sleep? Maybe watch TV, read a book, go for a walk, talk with friends, a hobby, exercise, shopping, cleaning, or (my favorite) organizing. In order to meditate more fully, we need to be done with all these things.

As the Tao Te Ching 38 says, “doing nothing, yet nothing undone”. We will never get to the bottom of our to do list so we have to decide this is “done enough” for now. Meditation practice is when we can strengthen our resolve and ability to set things aside for now. This is khanti, the highest virtue we can cultivate according to Buddha (khanti paramam tapo titikkha), translated as patience, forbearance, or persistence. I think for a rajasic person it’s patience and for a tamasic person it’s perseverance. While we sit, a rajasic person may be struggling to remain still without thinking of all the things worthy of thinking, and thereby can’t settle down. Whereas a tamasic person might be slowly sinking into sleep and will need to continue bringing their attention back to center over and over again, persevering. And one last thought, we can’t always force our self to meditate. That’s good initially, but eventually we have to let go the effort of that force. Practically that means we have to be free to choose to meditate without any “because I should”. A simple parallel reveals how we miss this so much. Many dog owners control their dog with a leash so they don’t run away, act aggressive, etc. But that’s not dog training because the dog has no choice when being controlled. Dog trainers tell you that you have to give them the choice and reward them when they choose correctly. After some time, the leash is only used to communicate the command not to enforce control. Can we do that with our own mind? I think it naturally happens when we start to crave meditation just simply because it’s so good.

- 9/25/23

At my high school reunion this weekend (link requires Facebook login), I heard many life stories and was impressed with the variety of issues and difficulties people have overcome or are still facing. It’s easy to forget when we surround ourselves with folks with whom we have a lot in common, but we really are so very uniquely individual. The same is true when we meditate. The tensions and obstacles that we hold in daily life have to be released, resolved, or temporarily set aside in order to settle into a deeper experience of alert tranquility. I often talk about how many people think too much and it’s hard to get our of our head and just sit. But others are quite the opposite and are so very sensitive to the conditions of their body and senses that they can’t just ignore them and be present. In finer detail, each person has a unique path from their daily life state of mind to the heavenly content and vibrantly aware state of mind called of jhana. Traditionally in Zen centers, those things can be discussed in private one-on-one discussions with the teacher where both can be very specific. But there are always lectures, books, dharma talks, etc where the audience is wide. In those cases we have to be selective in the advice we listen to by knowing what our difficulties are.

- 9/18/23

Retreats these days are kind of a vacation from daily life. We hear in ancient times, stories of persons going off to the wilderness, a monastery, ashram, temple, etc for years to totally transform their sense of self. Buddha’s 7years ascetic life in the wilderness, The missing years when Jesus may have trained with mystics in the Dead Sea. Even my teacher, Shibuya Sensei lived about 4 years in the wilderness of Hokkaido. These are drastic life-changing turns, that we rarely do while we seek to be more enlightened, succeed at work, maybe raise a family, stay healthy and beautiful, and have fun all the while. That’s ok, no matter how driven or lazy we are, eventually we will get there; there’s no deadline and no rush. But when we suffer and realize we can’t fix the circumstances, we are motivated to hurry up and get free of it. So typically we could use a retreat as a time to make that extra effort, and even if we don’t reach enlightenment we will be more settled physically, emotionally, mentally, and have a clearer sense of who we are and what we stand for. Returning to our daily efforts with that clarity and wholeness is quite valuable in the short as well as the long term. Retreats differ of course. Corporate retreats, yoga retreats, physics conferences, Chapel retreats, Zen retreats, and the retreat we did last year. They differ in cost, duration, amount of time spent in practice vs socially, as well as venue and purpose. This year’s retreat will center on three two-hour meditation periods with an hour after for solo contemplation. We’ll reserve the meditation hall for greater silence and continue being social at mealtimes. This seems like the right amount of challenge and rest for us for a 2-day retreat.

Going back to another story in ancient times for inspiration, Hokyoji temple in Japan is the #2 Zen headquarters and was founded by Hokyo Jaquen back in the 13th century. He emigrated from China when Dogen returned to Japan with Zen, but after Dogen passed, he was disillusioned with the level of practice at Eiheiji monastery (#1) and went into the deep wilderness on his own. Meditating on a large rock, he lived with a dog and a cow there for 18 years before a local samurai lord discovered him and asked him to teach. This led to Hokyoji. When Shibuya Sensei was young and seeking, he went to Eiheiji and Hokyoji and studied under Hashimoto Roshi. He too was disillusioned with the level of discipline when he saw how no one really practiced when the master was away, and left for Hokkaido. Are you seeing a pattern? When a person is really driven to find the solution to themselves, eventually they have to be alone with themselves. Meditation is the method, and jhana is the depth of the meditation which is the message that really matters, but each of us has to get the message by experiencing it and apply the method to use that depth of contentment to transform our personal suffering into a new sense of self. In my own life, I spent 10 years (off and on) living in a small town in Washington state, working in a remote underground former missile bunker with a couple other scientists. This was like a life retreat for me, physically apart from all the efforts I was involved with in Southern California. I was definitely a different person as a result, more settled on what mattered to me, more content about who I was, more relaxed about everything else.

- 9/11/23

A couple questions came up at the workshop on Saturday that made me think: how long do you meditate for? and what psychic abilities do you have? After some thought I realized these are excellent questions to ask of someone who’s teaching how to develop psychic abilities or to have good regular meditation practice. But I am doing neither here. My message is simply jhana. Yes, a good regular meditation practice will be good for almost anyone. But it is not required nor perhaps even helpful for you to discover jhana. I’ve often found a break from practice leads to a clearer, harmonious and enthusiastic practice when I return to it. Each of us is different and regular practice may help you get jhana or may not. The obstacles we bring to meditation are overcome by our own effort when we are ready and willing to overcome them. How long does it take to be ready and willing to overcome your fear, trauma, desire, etc. When you do experience jhana, and after some time practicing it you recognize it clearly and experience it regularly, then everything else will get simpler and I trust you will figure everything out. I’m sure you are thinking…”jhana may be there in my distant future but meditating now helps me feel more centered and I need a regular practice to support my challenging life.” As you face the obstacles in your life, why start with the small ones when they will all become irrelevant when you solve the big one? When you discover how to be settled to the degree of jhana, it’s the same; the smaller challenges fall off you like water. Spending your time overcoming the small things is really just biding your time until you are ready to be truly content. You CAN do it.

- 9/4/23

What does Buddhism say about psychic and medium abilities? Well, first of all there’s the terminology; Siddhi or Rddhi is the Sanskrit term used. There are many lists of these supernatural powers, and many examples of them being demonstrated by Buddha and others back in 500BC. There’s also a text of the biographies of the 84 Mahasiddhis (Buddhist psychics) available now with the title “Masters of Mahamudra” from about 1000AD. But later, for instance in a Zen monastery of the 1700’s, you would be kicked out for practicing these abilities. Why? Well, if you go back to what Buddha taught, he said basically that practicing psychic abilities was not as valuable as as learning to care for yourself and others. Zen monasteries grew to become very focused and determined to reach that goal and don’t allow tempting distractions like these abilities. You can see that if the reason you strive to develop such a skill is because it makes you feel good about yourself, then maybe you can’t afford to fail. That leads to delusion, which is the #1 danger of developing those skills according to Rev. Larr who founded the Chapel in 1972. There’s also the pitfall of the consumer of psychic advice, which Hollywood and our culture encourage. Here you could become addicted to finding out what you “should” do; from your life’s goals to what you should buy at the grocery store. So what’s the good side? Rev. Larr’s #1 reason to learn medium skills was to avoid accidentally crossing over by being sensitive to warnings about accidents and such. His #2 reason was that the experience of being a medium removes the fear of death. But it’s tricky to avoid the ego attachment, and I’ve seen many fall into it over the years, and almost none recover from it. The bottom line as I see it is that as you get more settled with yourself and the world, everything gets simpler and easier, and some things that appear supernatural become natural for you to experience. We’re just a part of an evolving Nature, and suffer when we get stuck on specifics whether it’s psychic abilities or more money.

- 8/28/23

Like a doctor, Buddha diagnosed life as dukkha (pain, suffering, dissatisfaction). What’s your solution? How can you be not-dukkha? I recently watched the movie based on the book Eat Pray Love which seemed to me to be a random collection of aphorisms. The main character learns the joy of doing nothing in Italy; to eat and indulge without worrying too much. Then in India she learns to express devotion and surrender control and forgive herself. Then in Bali it seems she gets her divine reward for growing in those ways by falling in love and letting go a little more. It reminded me of the world’s largest collection of ancient aphorisms, which you can find at the ruins of the temple of Apollo in Delphi, Greece. Here between the 8th century BC and the 4th century AD, priestesses gave inspired advice to emissaries from around the world. The aphorisms and maxims are inscribed in ancient Greek on the pillars all around the ruins ; here are about 150 of them, though the most famous is “Σαυτον ισθι” (Be/Know Yourself), because Socrates often quoted it. The trouble is, there are too many instructions, right? What is YOUR answer to Buddha’s diagnosis? As an example, “forgive yourself” from the movie is great if that’s what you need. But for a narcissist, forgiving themself is the wrong direction — they probably need to feel even more responsible. Even the advice I share about meditating can only apply to some of you. ‘Pay more attention’ may be the right direction if you tend to drift off, but may be the wrong direction if you are overthinking things. So, where are you now? What is your right direction to be not-dukkha? We have the Ashtanga yoga opening chant that venerates the “jungle physician” to cure the delusion of samsara. You might think sukkha (happiness), being the opposite of dukkha is the solution, but facing life’s challenges with a joyful lighthearted ever-positive attitude is still only good specific advice to where some of us are. Sometimes we need to face things with a serious and determined mind and admit that the situation is truly tragic. Being happy is not always the cure for being unhappy, but being content is the middle path. How can you be content? Let’s find and create that now as we meditate.

- 8/21/23

As your practice develops, here are some common steps people go through. First take responsibility and control. Take responsibility means that you realize that the answers are not out there; you stop searching so much and start looking more at your own mind. Take control is a deeper step where you stop sitting alone with yourself just waiting for answers to come to you; instead you might seek to understand why you do, say, and think the things that you do. Be careful here not to get too analytical; understanding requires observation but does not require analysis. Second, be mindful and be still in your meditation. This is the same thing I’ve been saying “pay attention and let go”. We do these things every day, but typically not at the same time. Here’s a handy chart:

holding tight letting go attentive sharper, tired? jhana not looking at yourself hurt yourself? to sleep? Third, consider what you are clinging to: life purpose/goals, personality drives, or biological needs. Here’s my own list of biological needs: a) to be social, perhaps with romance, b) wealth, which supports eating and sleeping, c) health and moreover comfort, d) safety and freedom to roam. For this audience, I’m guessing that unless you are facing a recent change you can probably let go of a) and b) pretty easily, and you probably don’t really worry about d) so much. But health and comfort are probably quite a challenge. When you meditate it’s not a matter of being so perfectly comfortable that you attain jhana, it that you let go of the ongoing discomfort, get jhana and then everything is exquisite even pain. So you have to decide that you are comfortable ENOUGH for now, then let it go. Here it’s important to make the distinction between good pain (that is letting you know somethings going on and maybe keeps you from falling asleep) and bad pain (that heralds a possible injury due to too much full lotus or something). Common sense: don’t injure yourself. So once everything is good ENOUGH, you let it all go and then jhana is simple: just breath with your whole body and mind.

- 8/7/23

As we grow in our meditation practice, I find we learn a few pivotal things. One is that we stop searching for the perfect cure or miracle or teacher and accept that we have to change ourselves in order to be happy. We’ve read enough books, listened to enough podcasts, attended enough workshops, and now we have to face ourselves and actually do the work. After we realize that, when we meditate we focus our attention inside ourself, because we know easy answers are not out there. We can’t just give up control to something or someone else. But this realization has a deeper layer that we eventually get. Initially we turn inward and exert our control over ourself while we meditate by controlling our breathing, insisting we don’t move at all, maybe even forcing our mind to avoid thinking things. This is kind of a strain. After 30, 40, 60 minutes we’re exhausted, sweating, but feel great because we’ve overcome a challenge. Our mind feels clearer too, so we ‘know’ we’re doing the right thing. That’s great but the deeper layer is that having control but refraining from exerting it feels even more amazing. When we allow ourself to be, but remain vigilant and capable of enforcing restraint, we stop the effort part of effort and conserve energy. Imagine you are a young adult in your first car. It feels so great to drive and be able to go anywhere and the roadside passing by as you speed down the road is quite a thrill. I think it has to do with sensing many things changing per second. Would a slow roller coaster be as exciting? Well, in meditation, when you sit vigilant but allowing, the multitude of details in each moment become more apparent. The same powerful thrill (without the adrenaline) of perceiving with great lucidity yet remaining steady transforms a moment from boring to bliss.

- 7/31/23

Thinking about what I might teach at the half day workshop we’re planning in Encinitas, I considered my expertise which is 4-fold: Physics, Yoga, Spiritualism, and Meditation. I always felt one should not rely on one part of their life for confidence alone and ended up relying largely on these 4. That way if there were a crisis in one school or with one relationship, I could continue confidently with a sense of self from the others. Anyway, thinking about how to combine these 4 into one workshop reminded me of the crazy names you come across these days and I came up with my own humorous twist as a joke: ‘the quantum yoga of enlightened ghosts: is yoga quantized? can a ghost reach enlightenment? do ghosts practice yoga? is enlightenment quantized?’. You know, the word quantum gets a lot of misuse because people don’t know what it means. It means that things come inn specific sizes or quantities: like apples. Generally trees produce integer numbers of apples, and rarely 3.183 apples on a branch. So you could say apples are quantized. The big breakthrough last century was when we considered maybe electrons can only be in specific energy levels around atoms and when they go between them they emit specific frequencies of light. This dramatically explained the color spectrum that ionized gasses produce such as the Aurora Borealis or a fluorescent light. Well, when we think about our mind, consciousness and meditation it turns out that we are not quantized. Typically we say I, you, them and count the number of persons present as integers. But inside your mind are competing processes for a sense of self, so we are more than 1. Plus we overlap with each other in a number of ways. It’s really quite complicated and no one can do the math yet for a fully non-local field theory of identity. But we can experience it even if we don’t understand it. When we experience jhana we are being the whole instead of being the part we normally identify with. Let’s do it!

- 7/24/23

Meditation is a specific practice and practice is a part of your life, just as jhana is temporary enlightenment and enlightenment precedes pari-nirvana (merging with the Universe in final cessation). So just as we explore ourselves and learn how we are holding ourselves back from jhana in meditation, we discover how we are creating our suffering in our life. There will always be pain, imperfection, and disharmony in life because life is in motion and these are symptoms of motion. But our personal experience of life can be very different depending on our perspective and motivation. To that end it’s good to see yourself clearly and find your balance. Personally I work full time analyzing data, which is heavy on the concentration and weak on the emotions. So after work I can easily find myself weeping at the silliest telenovela video. My body-mind seeks balance and learns toward emoting. It’s nothing personal, just cause and effect. Here on Mondays I’ve been pretty serious so tonight in the spirit of balance, I’ll share my collected meditation jokes for fun. Here are a couple of my favorites:

- 7/17/23

I was surprised when I learned that Yoga philosophy came after Buddhism, since I thought it was part of the Vedas from <1000BC. In fact Patanjali wrote the Yoga Sutras around 200AD which was 700 years after Buddha. He knew Buddhism and Hinduism and combined them into yoga philosophy. I was also surprised that the Bhagavad Gita was written up through 400AD as well. So it makes sense that we talk about meditation within Yoga practice as well as within Buddhist practice. I shared some short excerpts from Kino MacGregor’s 30-day Yogi program (p120, p63, p104, p118), each relating to a different Kosha (sheath of your being). Remember Patanjali talked about quelling the fluctuations in your mind… in your koshas: which would be 1) disharmonious and illness in your physical body, 2) emotional upset in your energy kosha, 3) disturbed thinking in your mental kosha, 4) questioning your values and beliefs in your kosha of knowing, and 5) doubting your identity and contentedness in your bliss kosha.

- 7/10/23

Yesterday there was a nice article on NPR about Buddhists and the “mindfulness industrial complex” that noted mindfulness is only one step of the 8-fold path. These days everyone teaches “mindfulness”, the common translation of the Pali word Sati (Smrti in Sanskrit) which Sensei and I prefer to translate as wholeheartedness. The 8-fold path has some familiar Sanskrit words in it, and I recommend the translation website for spoken Sanskrit. Each of the 8 starts with samyak (Sanskrit. or samma in Pali) meaning right or correct. If you see “sam” that’s usually what it means.

1) …drsti = gaze, view, as in understanding, which we recognize from asana practice (where is your dristi?)

2)…samkalpa = determination or intention

3) …vac = speech. In Pali it’s vaca is like voice.

4) ..karmata = action. you know karma = action.

5) …ajiva = livelihood. This is an odd one like an idiom. a-jiva literally is not-alive, but the meaning is livelihood.

6) …vyayama = effort, exercise as in what you do at the gym.

7) … = mindfulness/wholeheartedness. Be present; know what you are doing while you do it.

8)…samadhi = literally concentration/unification, epitomized by jhana.The question came up this week, can a person can get jhana seated in a chair or is full lotus required? I mentioned on 6/12 the story of Buddha’s final moments (see part 6 section 9). Here we have his disciples watching him in jhana as he lay on his deathbed. So certainly you can get jhana without full lotus posture if you are enlightened. So I gave it a try this last week and succeeded without too much difficulty. My mind simply stops caring where my limbs are as it moves toward jhana. If you have never experienced jhana or if you only experience it now and then in your meditation, then you really need to express your body-mind’s “effort” toward jhana. And wrapping your body up tight is excellent for that. (remember your mind will settle if you stop stirring it and allow it to come to rest, but there’s a little more needed to go deeper than your common resting point. That little more is the nudge of effort I’m referring to here).

- 7/3/23

These long meditations of 30-60min differ from the short 5min ones like at Chapel because we are trying to confront the obstacles that keep us from perfect stillness or jhana. And here we see the parallel between meditation and life in general. The same obstacles keep us from being happy, free and spontaneous and lead us into various painful suffering experiences. So let’s consider obstacles. You might say life is about relationships. With people, objects, circumstances. An example is your car. Typically you identify part of yourself as the person who drives that car, so when you get a new car you feel a little changed, a little like a new person. Same with clothing, homes, jobs, degrees, relationships, etc. You find that the specifics change while the theme persists, because you still have the same relationship to mature, grow, learn from. They often say this when you find yourself dating the same kind of wrong person, but it’s true in all parts of life. So what are your limits? Yoga is about facing your limits not extending them. It’s more important to develop a better relationship with dropbacks like not being afraid of them, than it is to be able to do dropbacks. The same is true of most asanas. How do you feel about a deep twisting pose like Marichiasana D? Each time you practice you can feel in more harmony with it, regardless of increased flexibility, strength, balance, etc. If you’re lucky enough that your limits don’t have the upper hand, then you’re not lost in panic or despair. In a sense you gain confidence by facing your limits. Real confidence, not the fake confidence you can get by pretending. Then once you are confident you can question the sources of confidence which include more than just the limits you’ve learned to be comfortable with. It’s like considering your attachments. For me I gained confidence from affection, money, college degrees, ordinations, appearance, life-skills and traveling, other specific skills, my parents, mentors, friends. Then when I ask why, I delve deeper into how I get confidence from each. That’s part of knowing myself which just by knowing, generates more confidence. Then of course sitting in jhana permeates me with confidence.

- 6/26/23

Why retreat? What is the purpose of going on a meditation retreat? A few things that came to mind are: 1) It’s a time apart from diversions and a chance to try better. Meditating at home is good, but also more challenging because the things we care about surround us – plans for a trip, family concerns, maybe work. When we go somewhere to meditate like a temple, studio, friend’s house, or a park, those things are less apparent and thereby easier to drop from our attention. I say here try better because try harder and try more are not really helpful as we apply effortless effort. 2) A chance to share advice with each other in person. Each of us has specific expertise, unique perspectives, and our own ways of expressing things. It’s wonderful to support each other and particularly in person. 3) it’s fun. At the weekend retreat last year, I think everyone was refreshed and enthusiastic in sharing the experience, the cooking, and the time away. This camaraderie is a great inspiration for practice. Some other ideas you mentioned included 4) hearing other viewpoints and discussing them like we did at the Sambuddhaloka temple with the monks. I’m looking into 3 retreat type events over the next 3 months and will see if there’s interest in each.

- 6/19/23

The problems we face in life generally don’t require us to SEARCH for hard-to-find solutions or solve COMPLICATED issues, rather they require us to be CLEAR-HEADED to see the simplicity of it. So how do we get clear-headed? After sleeping well, we wake up and have a cup of coffee, take a shower, exercise, eat well, etc. Universally, each of us needs to feel safe from violence, in good health, have food, sleep and close friendships. Basically we need to feel OK and loved. If we don’t have these biological needs, it can be hard to be clear-headed, but as we learn to center our self we can get there in less favorable circumstances. That’s where meditation comes in. Meditation as training for an hour to learn how to wake up, not meditation as a moment to relax and let go like you would at the spa. Meditation is confrontation. We face our self vulnerably confident. Many Zen stories talk about this confrontation with metaphors like swallowing a molten ball of iron – you can’t spit it out and you can’t swallow it, so what do you do? You have to persist in the confrontation. Similarly, Sensei wrote about the Tiger Canyon where his answer was to make friends with the wolf. This confrontation is what our instinct pushes us to avoid, but eventually it’s too painful to ignore it. Pain is thus our natural motivator. Physical pain is useful in that sense because it urges us to take actions we need to, and in meditation physical pain is useful to help us pay more attention and be more alert. On the down side, it also makes it harder to relax and let go. My own experience of pain in meditation such as pain in the knees while sitting in full lotus, is that it’s intimately tied to fear of injury. This could just be me, but I think it’s a common experience. Once I face and dispel that fear, knowing the pain is not a sign of impending injury, the sensation actually abates. Then of course when I focus into deeper meditation, such things as pain, hunger, sleepiness all drop away as irrelevant objects of attention. This is Dogen’s, “all of a sudden body and mind drop away” and the entry to jhana.

- 6/12/23

Lots of people write about jhana even if they have never experienced it because it’s so much a part of Buddha’s teachings. On his death bed (see part 6 number 9), Buddha was observed by his disciple Anuruddha to enter each of the 8 jhanas then pass away. Some of what I’ve heard from students of the Vipassana tradition created by Mr. Goenka contradicts what I know of jhanas by claiming that each can be practiced separately as distinct exercises. I know them to instead be like signposts as you settle deeper into your self. It doesn’t make sense then to “practice 4th jhana” without calming your mind to the degree of 3rd jhana first.

Well, I came across a website recently describing the jhanas that I think is very good. I think it useful to talk about it here, so we can get specific about the details and therefore better evaluate our own experiences (like I spoke about last week). I believe the author experiences it regularly based on what he’s written and my own experience of jhana. I particularly noticed that he comments on the above misunderstanding that he observed as well. A couple other things seem different to me but that’s to be expected of two persons writing about their experience of the same thing. First he writes that the senses do not work in jhana, but he practices with eyes closed. I practice with eyes open and the senses appear to work fine for me. It’s my experience of the world that changes in jhana. I experience it all at once in a gestalt way, rather than experiencing this sound or that image. Second, he mentions a lasting effect, persisting for hours or even days, whereas I find myself returned to everyday mind much sooner. It may be that I’ve ‘gotten used to it’ in some sense and move back and forth more quickly than I did when I had that first life-changing experience many years ago. Lastly, his descriptions of the different jhanas seem to be different numbers than what I experience. Specifically, we line up on 1st and 2nd jhana but my experience of 3rd jhana sounds like his 6th jhana having the quality of merging into non-dual experience. Anyway, I encourage you to read his website and hear about the experience from more than just me. You might also look it up in various places such as “Buddhist Dictionary” – Nyanatiloka.

- 6/5/23

How do you know if you experienced jhana? Traditionally your teacher confirms it. The Zen tradition traces this back to Buddha’s flower sermon, where instead of speaking to his disciples and students, Buddha simply held up a flower. Mahakassapa smiled and Buddha understood that he got the message. After centuries, this process has become codified into the “dharma transmission” of the Soto Zen school and the “Inka” ordination of the Rinzai school whereby the student is formally authorized to start a new school on their own and are then called “Roshi“. So how do they know? In a monastery, after maybe years of meditating together the teacher knows the student very well, and can tell when they experience something profound. What about direct psychic perception of the student while they are meditating? I’ve done some of that and found that it’s very difficult. If they are struggling with thoughts and feelings while meditating, then it’s pretty straightforward to sense it. Otherwise it’s difficult because when someone gets perfectly still inside themself, their mind disappears from view. So what about the words they use to describe the experience? Here you can only say when the words contradict jhana, and can’t say it definitely was it. Like stillness, if you describe it as a conversation or some dramatic progression, then that’s not stillness. If you describe jhana as including any struggling, striving, clinging, of suffering, then that’s not it. By definition, first jhana is when you are free and separate from all that. So, my teacher, Shibuya Sensei, was not impressed with the integrity of today’s institutions and felt that the formal transmissions were meaningless. He said, a student’s responsibility is to get the message from the teacher. And that led to the statement that nature, including all of us, are teachers bearing a message with our very existence, even if we do not know it. It’s up to you to get the message, to free yourself to experience jhana. When you do, it doesn’t matter who confirms it.

So how do you yourself know if you experience jhana regardless of confirmation from your teacher? You can read words others have used to describe their experience of it and see if it sounds the same. Here I’ve run into a couple discrepancies with descriptions written by persons I believe did indeed experience it. One Thai monk said he always sees a bright light. I’m sure he does, but I’m also sure that some others do not. So we have to be careful not to be too exacting in comparing words. Chapel teaches that you can evaluate your meditation afterwards by examining your mind. Specifically, if you were asleep then you feel groggy and return to alert consciousness slowly when you stop. Otherwise you are immediately alert. Also, if you are in a hypnotic state then you are not in control so that’s not it either. What if you disappear into stillness? This is the ideal “stage II” meditation from Chapel. Here you abide in a conscious state with no awareness. Time passes, but you are not aware of it until your meditation ends. Generally this is practiced for 5 minutes, not the usual 30-60 minutes. This is not quite jhana. There are two things to consider as you calm your mind: the degree to which it is calmed and the extent to which it is aware. If you shrink your circle of awareness (e.g. by closing your eyes), then there is less extent that needs to be calmed to reach perfect stillness. Jhana is more pervasive than this because you remain open and aware of your mind, your body, your senses, your surroundings. All of those things can be very distracting and prevent you from getting perfectly still. It may seem impossible, but you can do it. It is much harder. It’s worth it. Jhana includes the feeling of bliss and rapture in the first stages. Sometimes we may have an experience we think is jhana because it feels blissful, but remember jhana is euphoric but not intoxicating. I’d recommend Sensei’s book WAKEFUL pages 69-80 which describe the 9 jhanas.

- 5/29/23

Why do you meditate? I think it may have been the second serious question Sensei asked me after I started meditating with him. Basically, why are you here to meditate tonight? To give you context for the answer I gave, I’d just read the chapter on Hinduism in Huston Smith‘s “Religions of Man” (newest edition is “The World’s Religions”). He was born to American missionaries in China where he grew up, then after his Ph.D. had a career as a professor of Philosophy at MIT. This chapter has a nice section about how Hinduism enumerates the maturing wants of a person: 1) pleasure 2) success 3) service 4) liberation (moksha). This last one includes the desire to continue to be, to be aware and know, and to feel joy. The desire to know spoke to me at the time I met Sensei as I was completing my own PhD at UCLA in particle physics, as Huston wrote: “Second, we want to know, to be aware. People are endlessly curious. Whether it be a scientist probing the mysteries of nature, a businessman scanning the morning paper, a teen-ager glued to television to find out who won the ball game, or neighbors catching up on the local news over a cup of coffee, we are insatiably curious.” So I answered “curiosity”. I wanted to understand how the mind worked, how consciousness worked, how we ourselves work, and believed the answer lay in mastering meditation. I’d been meditating initially in the TM, then Chapel, and later the Soto Zen traditions all my life, but Sensei didn’t know that. He rejected my answer, saying something like “Curiosity is just a passing motive, something you might do on a weekend. What is your real motivation?” Fast forward to now. Here are some potential answers you might consider: a) I need to relax and let go, b) I need to get clear and motivated, c) I’m searching for answers and solace, d) I love meditation. The first two depend on what conditions you are facing in your life at the moment, and after years of practice and coming to know jhana, I find I simply love to just be present with that degree of perspicacity. So, what brings you to meditate at this time? There are no wrong answers, and the usefulness of the answer is to know your current self better. Your answers, like you, may mature in the sense Huston Smith described.

- 5/15/23

It’s important to be able to let go. In our daily life we have to let go to sleep, make love, or just enjoy the day. In meditation we have to let go in order to be fully present with ourself. Jhana and Enlightenment are basically the same, but with jhana you let go temporarily and with enlightenment you let go permanently. Let go of what? Of the attachments that obstruct you from being in perfect harmony, free and spontaneous to do anything you choose, from realizing universal consciousness. So then consider a short meditation period like 5 min compared with a longer one like 60 min. If you meditate for 5 minutes and spend them in jhana, that’s awesome, but unlikely for most persons. Instead some obstacle(s) will keep you from it, some anxiety you can’t let go, some concern you can’t stop worrying about, something in your environment or body that keeps grabbing your attention. In order to learn how to let go of those things you have to first separate yourself from them, and that requires applying keen investigation and holding steady clear perception of what the obstacles are. It does not require that you understand them or their mechanism; in fact that most always comes in hindsight. So don’t get lost in analytical reasoning and trying to “solve” for a solution. Well, when we meditate for a long time like 60 min, whatever we are holding on to that is holding us back starts to feel tired and worn out. That helps us perceive it. If we can hold our attention steady and crack ourselves open to let it go, then we’ve made the space for jhana. On the other hand we may get fully exhausted before we get that and have to try again another time. You may always exhaust without clearing the space, but don’t give up because anytime you might just let go and find it’s suddenly easy. After that experience, meditation practice becomes a real joy and new obstacles are welcome on the cushion and even in daily life. Eventually all obstacles are gone and you are just free and happy.

- 5/8/23

Some more thoughts on: A) the common perception of meditation, B) the 5 minutes twice-a-day practice prescribed in the Chapel curriculum, and C) the 30-60 minute traditional Buddhist breathing meditation practice. A) the superficial perception of meditation by a person just a little curious and trying it out is that it’s something you do in seeking a reprieve from stress/pain/etc similar to a vacation, time off work, hug, massage, etc. So it’s a way to obtain comfort. B) the Chapel practice of short meditations can help you overcome laziness since you only have 5 minutes to get still, but in general the purpose is to use your ability to create a steady and sensitive mind in order to practice other skills and generally live with more awareness. So you need to be comfortable in order to succeed in creating that. C) The lengthier practice where you allow your circle of awareness to remain open and hold your attention steady despite initially overwhelming distractions and disturbances is a confrontation with yourself. It’s opposite your instinct to seek comfort. Here we are training ourself, learning how to be comfortable with our discomfort. There are many layers of discomfort: physical like exercise, waking up early, eating; emotional like starting a new job, quitting a bad relationship; mental like public speaking, an exam or job interview; or our values like a career change, cross-country move, or grieving a death. It’s natural to grieve change (a death, a job, a relationship, money, etc) but we cling so tight that we get stuck on it. By facing it and creating peace we can get over it and move on with our life. This is true during an hour’s meditation practice as well – can you set aside your discomfort/trauma/story-line temporarily? Remember habits are comfortable, so when you go outside that circle (by choice or not), you have to face the discomfort. They say that post-satori practice (after the surprise of experiencing jhana for the first time) is moreso a welcoming of pain, embarrassment, difficulties that come to us in life as opportunities to create peace and comfort. There’s plenty to practice with. So as we start meditation, consider the easy circumstances you can arrange but don’t be obsessive about creating comfortable conditions because you can transform the experience.

- 5/1/23

The common perception of meditation is that it’s something you can do on occasion to relax, calm yourself, and improve your health. You may also hear something like, “it also helps you remember your connection to the divine by bringing that specific energy into you.” Here we consider the why of meditation more specifically. “Bring that energy into you” is basically a vague reference to 3rd jhana, where you experience yourself as merged into something greater than yourself. Practically speaking, to be in 3rd jhana you can’t just set an intention and have it happen to you. Life and meditation are like a staircase from Hell to Heaven and you have to take each step — there are no elevators where it happens to you just because you want it. You have to get 1st jhana first, and to do that you have to free yourself from every disturbance either negative or positive. Those are the stairs by which you can “visit Heaven” during a meditation period in jhana. That means, e.g. if you are concerned about the noise your neighbor is making while you meditate, you have to let that go and not care whatever noise they make. Also, simply plugging your ears may not do it, because you know that you are plugging your ears to avoid something disturbing and that’s enough to miss 1st jhana. It’s not a matter of arranging circumstances until you feel good, it’s a matter of feeling good regardless of circumstances. Rev. Gene Larr, in “Your Dawning Awareness” puts it simply: “Keep your mind still and allow it to relax….All distractions should be removed because you are going to have to still your mind and any of these distractions that can be removed before the practice of stilling, the easier it will be for you.” And here we move into the how of meditation. Keep it still and allow it to relax. Just as I’ve been saying, ‘let go and pay attention, at the same time’. The common instructions for meditating are to separate yourself from the external senses and let go of your thoughts. That’s good, but ANYTHING that catches your attention needs to be let go of to get to 1st jhana, not just the external senses. Typically a person who hasn’t meditated or is not too settled at the time is most distracted by external sounds, etc. But after some practice or in a more settled state, I see folks more often get caught by their reasoning mind mulling over problems, memories, etc. On the other hand some people get more often caught by how their body feels. There are many techniques and crutches to help with specific things, but in the end you have to let those things just be and realize you are independent of them. 1st jhana is just the sudden sensation of that freedom, when you feel your “body and mind dropped off” as Dogen Zenji wrote.

- 4/24/23

Ilene shared a video and discussion of their amazing spiritual journey to walk the Kumano Kodo World-Heritage route in Japan. Here is her video of the pilgrimage.

Also, I shared the “Spring Breeze” poem and story that Shibuya Sensei often mentioned: Tsu-yüan (aka Mugaku Sogen 1226-1286AD) came to Japan, advised the regent to the Shogun, and established the Engakuji Zen monastery. While still in China his temple was invaded by soldiers of the Yüan dynasty, who threatened to kill him, but he was immovable and quietly uttered the following verse:

乾坤無地卓孤筇

喜得人空法亦空

珍重大元三尺剣

電光影裡斬春風

There is no room in the Universe where one can insert even a single stick; I see the emptiness of all things—no objects, no persons. Honored be the sword, 3 feet long, wielded by the great Yüan swordsmen; it is like cutting the spring breeze with a flash of lightning.

It referred back to a poem by Seng-chao on the verge of death by a vagabond’s sword:

In body there exists no soul.

The mind is not real at all.

Now try on me thy flashing steel,

As if it cuts the wind of Spring, I feel.

Both these Zen masters had gone beyond attachment to life and death, knowing they are Nature – a spring breeze perhaps. - 4/17/23

We talked about Jay & Ilene’s pilgrimage in Japan. One topic was the idea of a Bodhisattva you “pray to” for help. In the first turning of the wheel of Buddhism, the cultural traditions around the Theravada typically have lay persons thinking they don’t have a chance to reach enlightenment this life so at least they can support the monastics who do. The second turning of the wheel started at the second Buddhist Council around 300-200BC where there was disagreement (eventually) over whether enlightenment could be attained by a person who was not a monastic and instead worked, married, and had a family. This later grew with Nargarjuna’s concept of emptiness in the Madhyamaka school around 200AD. By the time it reached China and NE Asia, the cultural practice of asking for help of those persons who have transcended the physical (no more rebirths), have almost reached final nirvana (cessation), but remain existing because they want to help others. They are the transcendent Bodhisattvas such as Quan Yin, Manjusri, Jizo, etc. When a person reaches full enlightenment they are a Buddha (awakened person), and a transcendent Bodhisattva has one last attachment – to help others. I hold to the idea that each of us has the ability to be perfectly content in the moment (jhana) and the chance to be perfectly content in our life (enlightenment), regardless of things like occupation, marital status, sex, health conditions. Although we can always ask for help – from transcendent Bodhisattvas, and other bodhisattvas (any compassionate person aspiring to help others), eventually we have to face and know our self in order to better know how to be content.

- 4/10/23

We scattered Sensei’s ashes in the poppy fields this weekend. Here’s a little write up I put on his website with some perhaps interesting topics to discuss this evening. We all talked about a couple questions regarding: 1) The difference in practices between Soto/Caodong and Rinzai/Linji Zen (just meditate vs koan study, group faces in or faces out). 2) The story of Siddhartha becoming a Buddha. Here’s a summary from Bhikkhu Bodhi:

“Just then he thought of another path to enlightenment, one which balanced proper care of the body with sustained contemplation and deep investigation. He would later call this path “the middle way” because it avoids the extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification. He had experienced both extremes, the former as a prince and the latter as an ascetic, and he knew they were ultimately dead ends. To follow the middle way, however, he realized he would first have to regain his strength. Thus he gave up his practice of austerities and resumed taking nutritious food. At the time five other ascetics had been living in attendance on the Bodhisatta, hoping that when he attained enlightenment he would serve as their guide. But when they saw him partake of substantial meals, they became disgusted with him and left him, thinking the princely ascetic had given up his exertion and reverted to a life of luxury.

Now he was alone, and complete solitude allowed him to pursue his quest undisturbed. One day, when his physical strength had returned, he approached a lovely spot in Uruvela by the bank of the Nerañjara River. Here he prepared a seat of straw beneath an asvattha tree (later called the Bodhi Tree) and sat down cross-legged, making a firm resolution that he would never rise up from that seat until he had won his goal. As night descended he entered into deeper and deeper stages of meditation until his mind was perfectly calm and composed. Then, the records tell us, in the first watch of the night he directed his concentrated mind to the recollection of his previous lives. Gradually there unfolded before his inner vision his experiences in many past births, even during many cosmic aeons; in the middle watch of the night he developed the “divine eye” by which he could see beings passing away and taking rebirth in accordance with their karma, their deeds; and in the last watch of the night he penetrated the deepest truths of existence, the most basic laws of reality, and thereby removed from his mind the subtlest veils of ignorance. When dawn broke, the figure sitting beneath the tree was no longer a Bodhisatta, a seeker of enlightenment, but a Buddha, a Perfectly Enlightened One, one who had attained the Deathless in this very life itself.

For several weeks the newly awakened Buddha remained in the vicinity of the Bodhi Tree contemplating from different angles the Dhamma, the truth he had discovered. Then he came to a new crossroad in his spiritual career: Was he to teach, to try to share his realization with others, or should he instead remain quietly in the forest, enjoying the bliss of liberation alone?” - 4/3/23

Who are you? We should be aware of how we define ourselves. I am a physicist, because I identify in part, with my education and first career. So here’s some advanced physics and its parallel with meditation and our sense of self. We don’t hear much about Relativistic Quantum Field Theory (RQFT) even though it was a major Nobel-winning breakthrough in 1965 when it was first created for electrodynamics (QED). We do hear about Quantum Mechanics (QM) from earlier in the century, when it was discovered that very small things like electromagnetic waves (light) are actually made up of small quantities called photons. We do hear about Einstein’s relativity, though his two theories get mixed up: Special Relativity (SR) = constant speed of light, so if you go very fast odd things happen, and General Relativity (GR) = his theory of gravity being a warp in spacetime. Well, RQFT was the unification of QM and SR and is technically called Second Quantization. Just like light being made up of photons and looks like a wave at larger scales, RQFT explained that every electron in the Universe is just a piece of the “electron field”. Same thing for each of the fundamental particles: a “proton field” a “neutron field”, etc. (technically each particle is a soliton in the corresponding field). Einstein thought it might go even further and all these fields might simply be different ways of folding up empty spacetime. OK, so here’s the parallel with meditation: what if like all the electrons being the same field, each of our selves are expressions of a Universe-wide field of consciousness? This is much different than saying we are all the same thing (e.g. a generic human?), and it is different from saying we are all connected (i.e. have an effect on each other). This is saying there is only one consciousness, and it is having experiences from multiple points of view. When we are in third Jhana it does feel like this, so I think it’s a reasonable theoretical explanation. But coming back to the practical aspect. Because we experience things with the mistaken belief that we are separate beings, we suffer. Buddha said we suffer from anicca, dukkha, and anatta (impermanence, dissatisfaction, no-self). We are talking here about anatta. So when we meditate we let go of all that defines us, so stop thinking of our self as the person who has this relationship, property, education, job, role, values, dreams, etc. Instead we become a universal person, or as Shibuya Sensei translated Buddha: “Sabbe dhamma anatta ti yada pannaya passati. Atha nibbindati dukkhe. Esa maggo visudhiya.” = “Achieve universal consciousness. Being not disturbed by anything at all.”

- 3/27/23

Discussion about the retreat on 3/25 and possible future retreats. Here are some zafu details that have come up recently. The props you use to sit in meditation should be sized to your skeletal system as well as to your flexibility. SIZE: A very large person with a large pelvis should use a zafu with an inner circle diameter of maybe 13″-15″ (typically called a “large” zafu). A very petite person with a very small pelvis — maybe 7″-9″ (“small”). Most everyone is in the middle at 10″-12″ (“medium”). For example the one I am using now is advertised as 14″ diameter (where they measure the full diameter) but has an inner circle diameter of 11″. We’ve found another supplier (a student of Katagiri Roshi) that looks even better. USE: When you use a zafu it’s important to only sit on 1/3rd of it, not on the top like some of the advertisements show (defeating the entire purpose of the zafu). Your sit bones should be on it and it should tilt your pelvis forward to give you a good upright posture. STUFFING: Zafus are overstuffed when you receive them, so you need to remove almost HALF the kapok (buckwheat husk stuffing is only good for short meditation periods; too hard for longer periods). The amount to remove depends on your flexibility. Try sitting on it for a while and determine if your knees get sore from too much weight on them (too much stuffing) or if your lumbar back muscles get sore because your pelvis is not tilted forward (too little stuffing). Similar considerations apply if you are using a meditation bench, etc. Happy sitting!

- 3/20/23

Happy Equinox! We had talked about the Faith in Mind Sutra, and someone texted me a line that stood out for them: “If the mind does not discriminate, all things are of one suchness. In the deep essence of one suchness, resolutely neglect conditions. 心若不異, 萬法一如. 一如體玄, 兀爾忘縁.” Think of this as ‘when you are meditating’. Basically when you find yourself present in the moment without weighing what’s better, figuring out this or that, judging, etc then you can experience ‘suchness’. It’s then that you should be determined to refrain from concern of conditions. And that leads you to awaken, to experience jhana in your meditation. So when you are really intent on something in your daily life that you can’t stop working on it, you are really focused. So how does the meditation instruction of “focus and let go” apply in that daily life situation? Is it good that you are focused or is it bad that you can’t let it go? The answer depends on if you have control….are you choosing to hold on or are you captivated and trapped by it? Remember, this is about moksha/liberation, freeing yourself from the fetters of your attachments so you have space to live and choose as you will. A couple are going to Japan for the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage, and are sure to see many beautiful places and temples. Bon Voyage! Here’s a painting my Hiroshige of some Japanese pilgrims:

- 3/13/23

How often do you meditate? How long do you meditate for in one session? What posture do you meditate in: sitting, standing, laying down? Do you meditate with eyes open or closed? Chapel prescribes 2/day, 5 minutes each, sitting in a comfortable chair, with eyes closed. A Zen temple might prescribe 9 sessions a day, 40 minutes each, sitting for 30 and walking for 10, with eyes open. Our practice here is 1/week, 60minutes, your choice of posture, your choice of eyes. Lots of variety. What are your personal practice choices? The important thing is to know why you are doing what you are doing (in life and in meditation): is it just a habit, a reaction, a conscious choice? Being mindful or enlightened means being aware of what you are doing and the context or why of it. Maybe with each Kosha: your body, energy, thinking, values, bliss…Bliss is an interesting one: if you lived every moment knowing what the bliss of jhana is, how could anything really bother you? But first you have to experience it. Practically, we are alive to face something: something painful, unpleasant, frustrating, embarrassing, confusing, etc. Eventually we overcome our fear. Here, meditation is practice/training: we temporarily overcome our obstacles. We can do it.

- 3/6/23

Concluding our look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. The Faith in Mind Sutra is an amazing Chinese Buddhist Sutra by Bodhidharma’s student’s student from around 600AD. This link has everything about it. I pointed out the biographical note on the author, the introductory note by Maezumi Roshi whom I studied with in LA, the original text in ancient Chinese, an interesting translation by a professor from Yugoslavia, and the more common translation by D.T. Suzuki whom Rev. Gene Larr met with for tea when they were alive. Remember Bodhidharma brought Buddhism from India to China around 500AD and is famous for sitting facing a cave wall for 9 years, and even more famous for having created the 5 schools of Zen, Tea Ceremony, Kung Fu and Tai Chi while at Shaolin monastery. Like the Heart Sutra’s discussion of form and emptiness, Faith in Mind discusses non-duality. We use this term in a few different ways: 1) to describe the view of polar opposites like good/bad, hot/cold, love/hate, 2) to describe how we represent reality with words (reification) so there are both words and the thing they represent (e.g. finger and the moon it points to), and 3) to describe the experience of jhana (3rd, 4th, etc jhana to be specific). Also, this meaning is the same duality in quantum mechanics where there is an observer and an observed. When that goes away, you are not watching yourself breathing…there is only breathing. Faith in Mind is also about turning away from concern about circumstances. We often forget that meditation is not a vacation or spa treatment where we are supposed to feel better as a result. Meditation is fundamentally training. We are training ourselves to wake up and be our whole self. Then everything feels better regardless of circumstance. Faith in Mind tells us that we can trust our mind to awaken if only we stop striving with circumstances.

- 2/27/23

Continuing to look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. Looking at the Kabbalah, let me start with some context. The world’s religions include the big 4 (Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism) is followed by 77% of people alive today. Despite only having 0.2%, Judaism is quite famous. It dates back to about 500BC (a little before Buddha) but is based on the preceding religion of Yahwism from the 1100’s BC. It’s texts are called the Tanakh which includes the Torah. Like the Sufi in Islam and Shingon in Buddhism, Kabbalah is a mystic esoteric sect (of Judaism). It formed about 1100AD in Spain and Southern France and the book Zohar is it’s primary text helping one to understand the Tanakh. The three forms of Kabbalah are the theosophical/theoretical understanding form, the ecstatic/meditative/experience of God form, and the practical/magical/harmonizing with heavenly forces form. To me these are like academic study, experience of jhana, and psychic experience. It’s remarkable how similar are: Ecstatic Kabbalah, Christian Mysticism, Jhana, and Yoga (“union with the divine”). Kabbalah refers to a celestial map of divine motivational forces: will, intellect, knowledge, and divine emotions called the Sephirot or Tree of Life where each circle represents a motivational force. A good book for seeing the parallels between Buddhism and Judaism is: The Jew in the Lotus.

- 2/20/23

Continuing to look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. The Mindfulness Tradition was created by Jon Kabat-Zinn in 1979 based on his study of Zen with Philip Kapleau (Yasutani Roshi’s lineage parallel to Maezumi Roshi in LA), Thich Nhat Hanh (Buddhist monk from Vietnam), and The Insight Meditation Society (Theravada Buddhist practice founded by Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfield, etc). Basically he made traditional Zen meditation practice accessible to folks in the US who were not comfortable with the Buddhist religious aspect of Zen. He did it through the U. Mass. Medical School as a pain management technique, later expanded to be a stress reduction technique in what they now call MBSR (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction). The UCLA dept. of Psychiatry center, Mindful Awareness Research Center (MARC, founded 2011), is in the same Mindfulness Tradition. However Thich Nhat Hanh’s mindfulness practice, Goenka’s Vipassana (= insight) meditation centers are not the same. As I’ve been saying, when you sit down to meditate the first thing that happens is you calm down and many meditate just for that purpose. The second thing is you center yourself. This is as far as pain management and stress reduction can take you in the Mindfulness Tradition. However Zen meditation goes one step further, where you can experience jhana, satori, and eventually enlightenment. For me these are practical human experiences not religious miracles or belief systems. I also often find teachings that work toward being more present forget that remembering the past and imagining the future are activities that you can be present with. Being present means knowing what you are doing. It’s just easier to attain when you limit yourself to the present moment unfolding in the world around you.

- 2/13/23

Continuing to look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. Here’s an introduction to the Upanishads, prompted by Noreen. I recommend a little Penguin book of excerpts. First, some rough context in time: Earth is 4,000,000,000 years old; life is 3,000,000,000 years old; the dinosaurs went extinct around 60,000,000 years ago; Hominid species like ours are about 5,000,000 years old and perhaps Homo Sapiens are 2,000,000 years old; written language started 5,000 years ago (=3,000BC); the first book was the Epic of Gilgamesh from ~2,500BC. Second, some context on early civilization: the main centers were along 4 rivers: The Tigris-Euphrates rivers and ancient Persian/Sumerian cultures, the Yang-Tze/Yellow river and ancient Chinese culture, the Nile river and ancient Egyptian culture, and the Indus river and ancient Indian culture. Lastly, from the ancient Indian culture we have the Vedas: writings from ~1,500 BC and the Upanishads: perhaps poetic summaries of the Vedas from between 800 and 200 BC. The Mahavakyas [Sanskrit: maha=great, vakya (from which we have the word “vocal”), so “great sayings”] are short phrases from the Upanishads. Ghandi revered the Isha Upanishad above all of them, and we have already gone through the Katha Upanishad. Today shared some excerpts from the Chandogya Upanishad including a favorite that I think spans Hinduism, Christianity and Buddhism:

“It is true that the body is mortal, that it is under the power of death; but it is also the dwelling of Atman, the Spirit of immortal life. The body, the house of the Spirit, is under the power of pleasure and pain; and if a man is ruled by his body then this man can never be free. But when a man is in the joy of the Spirit, in the Spirit which is ever free, then this man is free from all bondage, the bondage of pleasure and pain.“ - 2/6/23

Continuing to look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. The Heart Sutra is perhaps the most famous across all of Mahayana Buddhism. Read English translation Sensei helped me write in 1994. We chanted it together in Japanese syllables (Maka Hannya Haramita Shingyo). Intruduced Hakuin Zenji and his commentary on the Heart Sutra. It may seem irreverent, but that’s just pointing out our inescapable hypocrisy: The Heart Sutra says all forms are empty (of no particular significance) including sutras such as the Heart Sutra. Same idea as UCI professor Derrida’s deconstructionism of all written words, which he expressed in his book, ironically. The point is we can only know truth through expression in forms. It’s the same dichotomy as in the Vedic Purusha and Prakriti, the Japanese Ri 理 and Gi, and even perhaps the ancient Egyptian Ba (personality soul) and Ka (immortal soul). Some music using the Heart Sutra: in Sanskrit, and in Mandarin from Gg.

- 1/30/23

Continuing to look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. The Dhammapada is a nice famous collection of 423 short paragraphs from the Buddhist cannon. “Show and tell” based on Zen Mind Beginners Mind by Shunryu Suzuki Roshi (1904-1971). History of Zen in the US, Suzuki Roshi’s lineage, and how to meditate videos from SFZC. I chatted about the couple dozen places/books/and people I’ve known, in particular KannonDo where I started practicing Zen in 1990 with Les Kaye Roshi and Misha Merrill Sensei, a retreat in New Rochelle with Susan Postal Sensei in 2006 and my visit to Suzuki Roshi’s home temple Rinsoin in Yaizu, Japan with his son and heir Hoitsu Suzuki Roshi in 1994.

- 1/25/23