The common perception of meditation is that it’s something you can do on occasion to relax, calm yourself, and improve your health. You may also hear something like, “it also helps you remember your connection to the divine by bringing that specific energy into you.” Here we consider the why of meditation more specifically. “Bring that energy into you” is basically a vague reference to 3rd jhana, where you experience yourself as merged into something greater than yourself. Practically speaking, to be in 3rd jhana you can’t just set an intention and have it happen to you. Life and meditation are like a staircase from Hell to Heaven and you have to take each step — there are no elevators where it happens to you just because you want it. You have to get 1st jhana first, and to do that you have to free yourself from every disturbance either negative or positive. Those are the stairs by which you can “visit Heaven” during a meditation period in jhana. That means, e.g. if you are concerned about the noise your neighbor is making while you meditate, you have to let that go and not care whatever noise they make. Also, simply plugging your ears may not do it, because you know that you are plugging your ears to avoid something disturbing and that’s enough to miss 1st jhana. It’s not a matter of arranging circumstances until you feel good, it’s a matter of feeling good regardless of circumstances. Rev. Gene Larr, in “Your Dawning Awareness” puts it simply: “Keep your mind still and allow it to relax….All distractions should be removed because you are going to have to still your mind and any of these distractions that can be removed before the practice of stilling, the easier it will be for you.” And here we move into the how of meditation. Keep it still and allow it to relax. Just as I’ve been saying, ‘let go and pay attention, at the same time’. The common instructions for meditating are to separate yourself from the external senses and let go of your thoughts. That’s good, but ANYTHING that catches your attention needs to be let go of to get to 1st jhana, not just the external senses. Typically a person who hasn’t meditated or is not too settled at the time is most distracted by external sounds, etc. But after some practice or in a more settled state, I see folks more often get caught by their reasoning mind mulling over problems, memories, etc. On the other hand some people get more often caught by how their body feels. There are many techniques and crutches to help with specific things, but in the end you have to let those things just be and realize you are independent of them. 1st jhana is just the sudden sensation of that freedom, when you feel your “body and mind dropped off” as Dogen Zenji wrote.

4/24/23

Ilene shared a video and discussion of their amazing spiritual journey to walk the Kumano Kodo World-Heritage route in Japan. Here is her video of the pilgrimage.

Also, I shared the “Spring Breeze” poem and story that Shibuya Sensei often mentioned: Tsu-yüan (aka Mugaku Sogen 1226-1286AD) came to Japan, advised the regent to the Shogun, and established the Engakuji Zen monastery. While still in China his temple was invaded by soldiers of the Yüan dynasty, who threatened to kill him, but he was immovable and quietly uttered the following verse:

乾坤無地卓孤筇

喜得人空法亦空

珍重大元三尺剣

電光影裡斬春風

There is no room in the Universe where one can insert even a single stick; I see the emptiness of all things—no objects, no persons. Honored be the sword, 3 feet long, wielded by the great Yüan swordsmen; it is like cutting the spring breeze with a flash of lightning.

It referred back to a poem by Seng-chao on the verge of death by a vagabond’s sword:

In body there exists no soul.

The mind is not real at all.

Now try on me thy flashing steel,

As if it cuts the wind of Spring, I feel.

Both these Zen masters had gone beyond attachment to life and death, knowing they are Nature – a spring breeze perhaps.

4/17/23

We talked about Jay & Ilene’s pilgrimage in Japan. One topic was the idea of a Bodhisattva you “pray to” for help. In the first turning of the wheel of Buddhism, the cultural traditions around the Theravada typically have lay persons thinking they don’t have a chance to reach enlightenment this life so at least they can support the monastics who do. The second turning of the wheel started at the second Buddhist Council around 300-200BC where there was disagreement (eventually) over whether enlightenment could be attained by a person who was not a monastic and instead worked, married, and had a family. This later grew with Nargarjuna’s concept of emptiness in the Madhyamaka school around 200AD. By the time it reached China and NE Asia, the cultural practice of asking for help of those persons who have transcended the physical (no more rebirths), have almost reached final nirvana (cessation), but remain existing because they want to help others. They are the transcendent Bodhisattvas such as Quan Yin, Manjusri, Jizo, etc. When a person reaches full enlightenment they are a Buddha (awakened person), and a transcendent Bodhisattva has one last attachment – to help others. I hold to the idea that each of us has the ability to be perfectly content in the moment (jhana) and the chance to be perfectly content in our life (enlightenment), regardless of things like occupation, marital status, sex, health conditions. Although we can always ask for help – from transcendent Bodhisattvas, and other bodhisattvas (any compassionate person aspiring to help others), eventually we have to face and know our self in order to better know how to be content.

4/10/23

We scattered Sensei’s ashes in the poppy fields this weekend. Here’s a little write up I put on his website with some perhaps interesting topics to discuss this evening. We all talked about a couple questions regarding: 1) The difference in practices between Soto/Caodong and Rinzai/Linji Zen (just meditate vs koan study, group faces in or faces out). 2) The story of Siddhartha becoming a Buddha. Here’s a summary from Bhikkhu Bodhi:

“Just then he thought of another path to enlightenment, one which balanced proper care of the body with sustained contemplation and deep investigation. He would later call this path “the middle way” because it avoids the extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification. He had experienced both extremes, the former as a prince and the latter as an ascetic, and he knew they were ultimately dead ends. To follow the middle way, however, he realized he would first have to regain his strength. Thus he gave up his practice of austerities and resumed taking nutritious food. At the time five other ascetics had been living in attendance on the Bodhisatta, hoping that when he attained enlightenment he would serve as their guide. But when they saw him partake of substantial meals, they became disgusted with him and left him, thinking the princely ascetic had given up his exertion and reverted to a life of luxury.

Now he was alone, and complete solitude allowed him to pursue his quest undisturbed. One day, when his physical strength had returned, he approached a lovely spot in Uruvela by the bank of the Nerañjara River. Here he prepared a seat of straw beneath an asvattha tree (later called the Bodhi Tree) and sat down cross-legged, making a firm resolution that he would never rise up from that seat until he had won his goal. As night descended he entered into deeper and deeper stages of meditation until his mind was perfectly calm and composed. Then, the records tell us, in the first watch of the night he directed his concentrated mind to the recollection of his previous lives. Gradually there unfolded before his inner vision his experiences in many past births, even during many cosmic aeons; in the middle watch of the night he developed the “divine eye” by which he could see beings passing away and taking rebirth in accordance with their karma, their deeds; and in the last watch of the night he penetrated the deepest truths of existence, the most basic laws of reality, and thereby removed from his mind the subtlest veils of ignorance. When dawn broke, the figure sitting beneath the tree was no longer a Bodhisatta, a seeker of enlightenment, but a Buddha, a Perfectly Enlightened One, one who had attained the Deathless in this very life itself.

For several weeks the newly awakened Buddha remained in the vicinity of the Bodhi Tree contemplating from different angles the Dhamma, the truth he had discovered. Then he came to a new crossroad in his spiritual career: Was he to teach, to try to share his realization with others, or should he instead remain quietly in the forest, enjoying the bliss of liberation alone?”

4/3/23

Who are you? We should be aware of how we define ourselves. I am a physicist, because I identify in part, with my education and first career. So here’s some advanced physics and its parallel with meditation and our sense of self. We don’t hear much about Relativistic Quantum Field Theory (RQFT) even though it was a major Nobel-winning breakthrough in 1965 when it was first created for electrodynamics (QED). We do hear about Quantum Mechanics (QM) from earlier in the century, when it was discovered that very small things like electromagnetic waves (light) are actually made up of small quantities called photons. We do hear about Einstein’s relativity, though his two theories get mixed up: Special Relativity (SR) = constant speed of light, so if you go very fast odd things happen, and General Relativity (GR) = his theory of gravity being a warp in spacetime. Well, RQFT was the unification of QM and SR and is technically called Second Quantization. Just like light being made up of photons and looks like a wave at larger scales, RQFT explained that every electron in the Universe is just a piece of the “electron field”. Same thing for each of the fundamental particles: a “proton field” a “neutron field”, etc. (technically each particle is a soliton in the corresponding field). Einstein thought it might go even further and all these fields might simply be different ways of folding up empty spacetime. OK, so here’s the parallel with meditation: what if like all the electrons being the same field, each of our selves are expressions of a Universe-wide field of consciousness? This is much different than saying we are all the same thing (e.g. a generic human?), and it is different from saying we are all connected (i.e. have an effect on each other). This is saying there is only one consciousness, and it is having experiences from multiple points of view. When we are in third Jhana it does feel like this, so I think it’s a reasonable theoretical explanation. But coming back to the practical aspect. Because we experience things with the mistaken belief that we are separate beings, we suffer. Buddha said we suffer from anicca, dukkha, and anatta (impermanence, dissatisfaction, no-self). We are talking here about anatta. So when we meditate we let go of all that defines us, so stop thinking of our self as the person who has this relationship, property, education, job, role, values, dreams, etc. Instead we become a universal person, or as Shibuya Sensei translated Buddha: “Sabbe dhamma anatta ti yada pannaya passati. Atha nibbindati dukkhe. Esa maggo visudhiya.” = “Achieve universal consciousness. Being not disturbed by anything at all.”

3/27/23

Discussion about the retreat on 3/25 and possible future retreats. Here are some zafu details that have come up recently. The props you use to sit in meditation should be sized to your skeletal system as well as to your flexibility. SIZE: A very large person with a large pelvis should use a zafu with an inner circle diameter of maybe 13″-15″ (typically called a “large” zafu). A very petite person with a very small pelvis — maybe 7″-9″ (“small”). Most everyone is in the middle at 10″-12″ (“medium”). For example the one I am using now is advertised as 14″ diameter (where they measure the full diameter) but has an inner circle diameter of 11″. We’ve found another supplier (a student of Katagiri Roshi) that looks even better. USE: When you use a zafu it’s important to only sit on 1/3rd of it, not on the top like some of the advertisements show (defeating the entire purpose of the zafu). Your sit bones should be on it and it should tilt your pelvis forward to give you a good upright posture. STUFFING: Zafus are overstuffed when you receive them, so you need to remove almost HALF the kapok (buckwheat husk stuffing is only good for short meditation periods; too hard for longer periods). The amount to remove depends on your flexibility. Try sitting on it for a while and determine if your knees get sore from too much weight on them (too much stuffing) or if your lumbar back muscles get sore because your pelvis is not tilted forward (too little stuffing). Similar considerations apply if you are using a meditation bench, etc. Happy sitting!

3/20/23

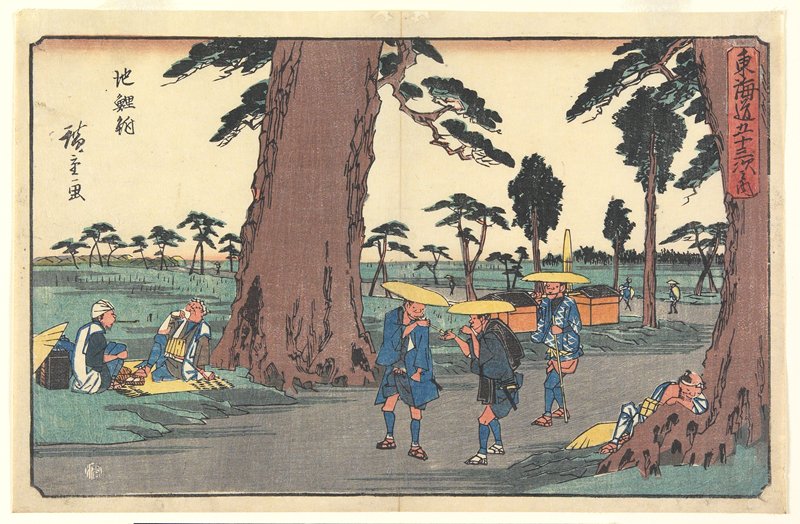

Happy Equinox! We had talked about the Faith in Mind Sutra, and someone texted me a line that stood out for them: “If the mind does not discriminate, all things are of one suchness. In the deep essence of one suchness, resolutely neglect conditions. 心若不異, 萬法一如. 一如體玄, 兀爾忘縁.” Think of this as ‘when you are meditating’. Basically when you find yourself present in the moment without weighing what’s better, figuring out this or that, judging, etc then you can experience ‘suchness’. It’s then that you should be determined to refrain from concern of conditions. And that leads you to awaken, to experience jhana in your meditation. So when you are really intent on something in your daily life that you can’t stop working on it, you are really focused. So how does the meditation instruction of “focus and let go” apply in that daily life situation? Is it good that you are focused or is it bad that you can’t let it go? The answer depends on if you have control….are you choosing to hold on or are you captivated and trapped by it? Remember, this is about moksha/liberation, freeing yourself from the fetters of your attachments so you have space to live and choose as you will. A couple are going to Japan for the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage, and are sure to see many beautiful places and temples. Bon Voyage! Here’s a painting my Hiroshige of some Japanese pilgrims:

3/13/23

How often do you meditate? How long do you meditate for in one session? What posture do you meditate in: sitting, standing, laying down? Do you meditate with eyes open or closed? Chapel prescribes 2/day, 5 minutes each, sitting in a comfortable chair, with eyes closed. A Zen temple might prescribe 9 sessions a day, 40 minutes each, sitting for 30 and walking for 10, with eyes open. Our practice here is 1/week, 60minutes, your choice of posture, your choice of eyes. Lots of variety. What are your personal practice choices? The important thing is to know why you are doing what you are doing (in life and in meditation): is it just a habit, a reaction, a conscious choice? Being mindful or enlightened means being aware of what you are doing and the context or why of it. Maybe with each Kosha: your body, energy, thinking, values, bliss…Bliss is an interesting one: if you lived every moment knowing what the bliss of jhana is, how could anything really bother you? But first you have to experience it. Practically, we are alive to face something: something painful, unpleasant, frustrating, embarrassing, confusing, etc. Eventually we overcome our fear. Here, meditation is practice/training: we temporarily overcome our obstacles. We can do it.

3/6/23

Concluding our look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. The Faith in Mind Sutra is an amazing Chinese Buddhist Sutra by Bodhidharma’s student’s student from around 600AD. This link has everything about it. I pointed out the biographical note on the author, the introductory note by Maezumi Roshi whom I studied with in LA, the original text in ancient Chinese, an interesting translation by a professor from Yugoslavia, and the more common translation by D.T. Suzuki whom Rev. Gene Larr met with for tea when they were alive. Remember Bodhidharma brought Buddhism from India to China around 500AD and is famous for sitting facing a cave wall for 9 years, and even more famous for having created the 5 schools of Zen, Tea Ceremony, Kung Fu and Tai Chi while at Shaolin monastery. Like the Heart Sutra’s discussion of form and emptiness, Faith in Mind discusses non-duality. We use this term in a few different ways: 1) to describe the view of polar opposites like good/bad, hot/cold, love/hate, 2) to describe how we represent reality with words (reification) so there are both words and the thing they represent (e.g. finger and the moon it points to), and 3) to describe the experience of jhana (3rd, 4th, etc jhana to be specific). Also, this meaning is the same duality in quantum mechanics where there is an observer and an observed. When that goes away, you are not watching yourself breathing…there is only breathing. Faith in Mind is also about turning away from concern about circumstances. We often forget that meditation is not a vacation or spa treatment where we are supposed to feel better as a result. Meditation is fundamentally training. We are training ourselves to wake up and be our whole self. Then everything feels better regardless of circumstance. Faith in Mind tells us that we can trust our mind to awaken if only we stop striving with circumstances.

2/27/23

Continuing to look at famous teachings about meditation to support confidence in your search for the answer. Looking at the Kabbalah, let me start with some context. The world’s religions include the big 4 (Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism) is followed by 77% of people alive today. Despite only having 0.2%, Judaism is quite famous. It dates back to about 500BC (a little before Buddha) but is based on the preceding religion of Yahwism from the 1100’s BC. It’s texts are called the Tanakh which includes the Torah. Like the Sufi in Islam and Shingon in Buddhism, Kabbalah is a mystic esoteric sect (of Judaism). It formed about 1100AD in Spain and Southern France and the book Zohar is it’s primary text helping one to understand the Tanakh. The three forms of Kabbalah are the theosophical/theoretical understanding form, the ecstatic/meditative/experience of God form, and the practical/magical/harmonizing with heavenly forces form. To me these are like academic study, experience of jhana, and psychic experience. It’s remarkable how similar are: Ecstatic Kabbalah, Christian Mysticism, Jhana, and Yoga (“union with the divine”). Kabbalah refers to a celestial map of divine motivational forces: will, intellect, knowledge, and divine emotions called the Sephirot or Tree of Life where each circle represents a motivational force. A good book for seeing the parallels between Buddhism and Judaism is: The Jew in the Lotus.